Workflow: Comprehensive Exams Preparation, Using Handwritten Notes and Scrivener

This is a walk through of the reading and note taking process that I’m following in preparation for Comprehensive Exams this Spring. Preparation includes reading 150 and 200 works selected by candidates in consultation an advisor and doctoral committee. The exams themselves are a series of three short essays completed over the course of a week. A question is sent via e-mail, and you have twenty-four hours to write and submit your essay. It’s not assumed that you’ll stay up for the whole twenty-four hours, but time is a factor, so it’s important to have notes and texts easy accessible and searchable.

I started my coursework thinking about Comps exams down the road, and I wanted to be able to easily find my class notes and reading notes and apply them during the exam. Things didn’t really work out that way, because it did take me a while to find what methods of note taking really worked best for me in the first place. So I’ve created this workflow all while looking backwards and wishing I had done something roughly like this all along. To be clear, because I have not yet taken the exams, I cannot vouch for the efficacy of this. However, I imagine that if you had no organizing strategy as of yet, or if you are a few years away from similar exams and would like to start preparing for what’s ahead, this might be useful.

I recognize that this is also a somewhat time-consuming process, and I’ve still got a lot of reading ahead. So I will disclaim right here that this could probably stand to be a bit leaner.

I’ve written each section header in an imperative, “Do this” tone for sake of clarity, however, just assume that each one of these is preceded by a very meek, very qualified,

“You know, I’m far from an authority on this, because I haven’t taken this exam…but here’s what I’m doing and hoping it will work…”

So yes, just imagine that appearing before each step.

1. While reading: take notes in the blank pages of the book (or, if borrowing the book, on a separate page). Use page numbers to start each note item, rather than a numbered list, and create separate sections to list page references for important topics, themes, or connections to other works.

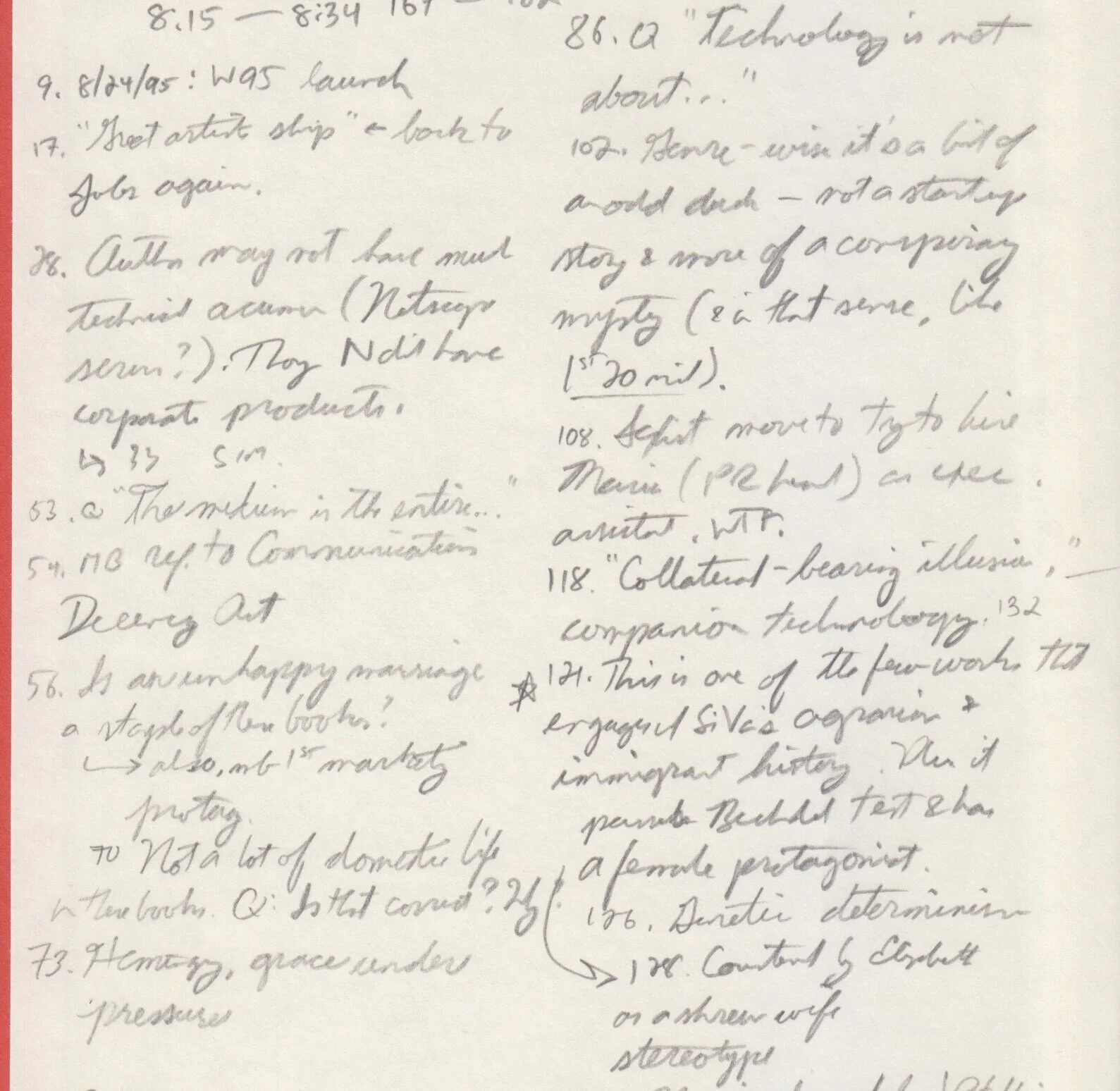

Part of my first notes page for The Last Best Thing, by Pat Dillon. I confess that the nicer the edition, the more awkward I feel writing in it like this.

During my coursework, I experimented with many different note taking methods, and have found that the above works best for me. Though I formerly used and reused plenty of plastic post-it flags, rarely did I find that they helped me find a particular page or passage in the midst of a seminar discussion. Marginal comments (though I still make those now and then) fell prey to the same problem. Better to have everything in one place, so that if I want to look through and see what I thought was important, it’s available at a single glance, and I can go to that page if need be.

A while ago, I had kept these notes as numbered lists, with the page numbers in parentheses. But I realized that, since I’m taking the notes as I’m reading anyway, the page number may as well be the number at the front of the note item.

So instead of the first note on the above page being:

1. “Great artists ship” <— back to Jobs again (17)It’s just:

17. “Great artists ship” <— back to Jobs againIs this absolutely essential?

Not really.

Does it make me happy to have eliminated a few excess characters?

Kinda.

Occasionally, I mark off sections of a page for notes or page references to a particular topic or theme. This can be hit or miss, because what seems like an important theme early on may fizzle out partway through the book, and it’s also easy to forget that something that catches my attention already has a separate section it should be entered into. Nonetheless, it does help jog my memory in terms of reminding me of at least a few things that I thought were important, and telling me where I can find at least one or two examples.

I use a similar section for noting connections to other works. I imagine it will be helpful to identify common themes or tropes across the works in my list.

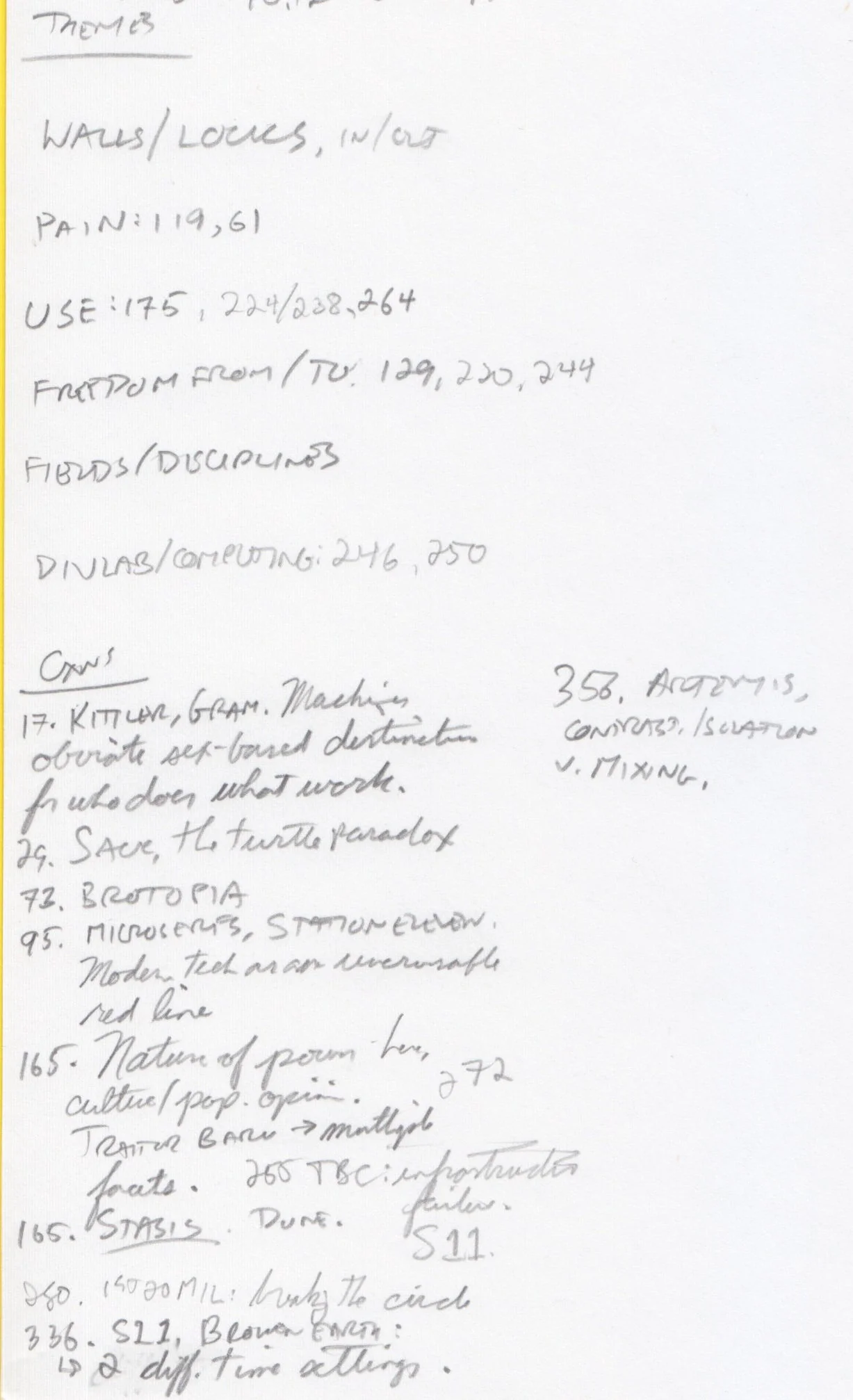

Themes and Connections notes page for Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed

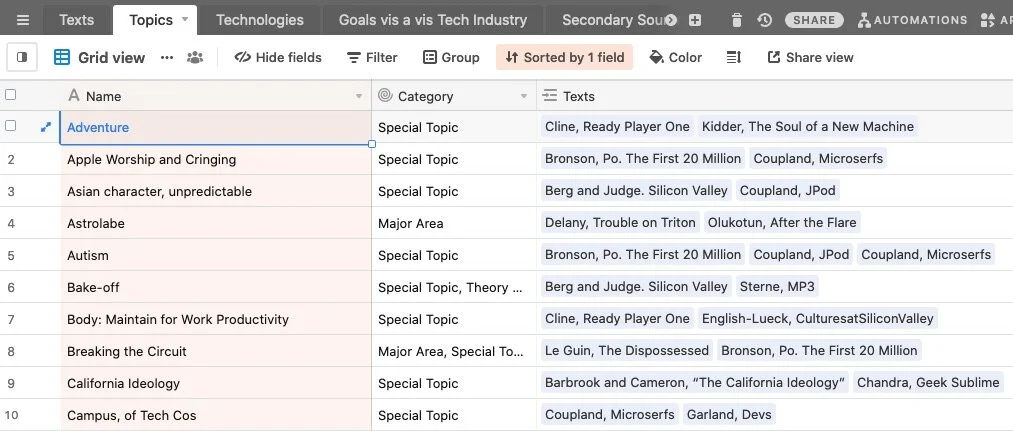

I’ve also starting putting these into an Airtable database. I have to confess, I hope this helps me, because it is quite fun to collect this stuff and see topic buckets like the below fill up. However, I confess that as I work on the database, it does feel like the part of this workflow that’s the most like fussing over something just for the sake of fussing.

2. After reading, write a page of notes and thoughts.

I’ve adopted this bit of advice from my advisor, and it was helpful throughout my last year of coursework. The key here is to not make these too long, and for me, that means limiting my time on them to roughly an hour to an hour-and-a-half for each work.

Caution: I have made the mistake before of looking at this task as typing down everything from my handwritten notes. This was usually a waste of time—while reading, it’s tough to know what is and is not important, so not every written note is going to be worth typing up. I found it better to make the typed notes process a separate thinking exercise in itself, in which, with written notes as reference, and with a little more distance form the text, I can synthesize what I’ve read and generate a few higher level thoughts and points.

I usually break my typed notes into these sections:

SummaryA short summary of the work, off the top of my head. This tended to be easier than I thought, because the most important stuff tends to stay pretty present.

For some academic texts, I’ve broken this up into chapter summaries, usually condensed to only one or two sentences.

Comments and ThoughtsTypically, four to five points about the text worth thinking about.

Key QuotesConnections to Other WorksAirtable or something like it may be the ideal way to keep track of these connections, but at least listing them in the typed notes means that you can find them easily. Scrivener lets you do this, and a MacOS Finder / Windows Explorer window may be able to get you a similar result.

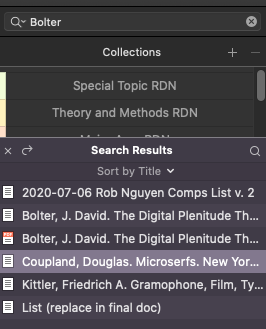

In Scrivener’s search field, click the magnifying glass dropdown arrow and select Search in:All. Typing into the search field will now populate with all items that include the search term anywhere in them. So in the below example, the notes I took on J. David Bolter’s book The Digital Plenitude appear, but all notes that mention Bolter by name appear also my notes on Douglas Coupland’s Microserfs and Friedrich Kittler’s Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. In both of those notes, I reference Bolter (albeit regarding Remediation and not The Digital Plenitude).

3. Save these somewhere where you can easily get to them later.

This is the more specific-to-me part of the workflow, and may be the least broadly useful. But for sake of speed (I actually should be reading right now), I’m just going to lay it all out as quickly as possible.

I gave Scrivener a test drive by using it for my seminar papers in the fall of 2019, and I’ve since used it for most of my writing projects. It creates a single space where I can put all my stuff pertaining to the exam, which means that when the time comes, hopefully, I’ll spend more time writing and less time rearranging, minimizing, and maximizing folders of notes.

I’ve followed these steps to collect and organize these notes:

Scan the written notes you’ve taken on the text, and label the file with some convention that you can use consistently throughout the exam preparation process. By default, I label my notes by their Chicago Style bibliography entry, and append “written notes” to the end of the title.

In Scrivener, create folders for each portion of your lists.

Save the scan to this folder.

Save the typed notes to this folder. By default, I label these notes by that same Chicago Style bibliography entry, but I append “RDN” to the end of the title instead. (This is not consistent nomenclature with the “Typed notes” terminology I’ve used in this post. If I were to start over, I might just append “typed notes” instead.)

Alphabetize by author last name (or whatever method makes the most sense to you).

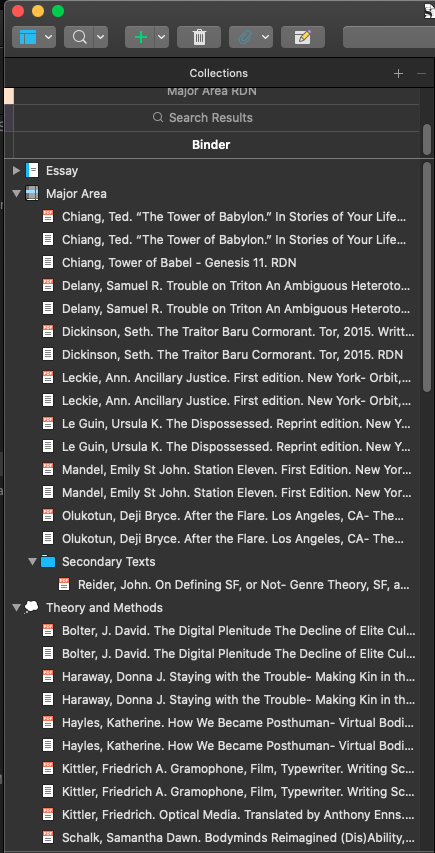

The result will look something like this:

I admit that there ought to be a lot more folders in these notes by now. Also, I don’t have a great method for wrapping notes on secondary texts into this. The best I’ve got is referencing the secondary text in the typed notes, and I can go find those in my Reading Notes folder if if I need them.

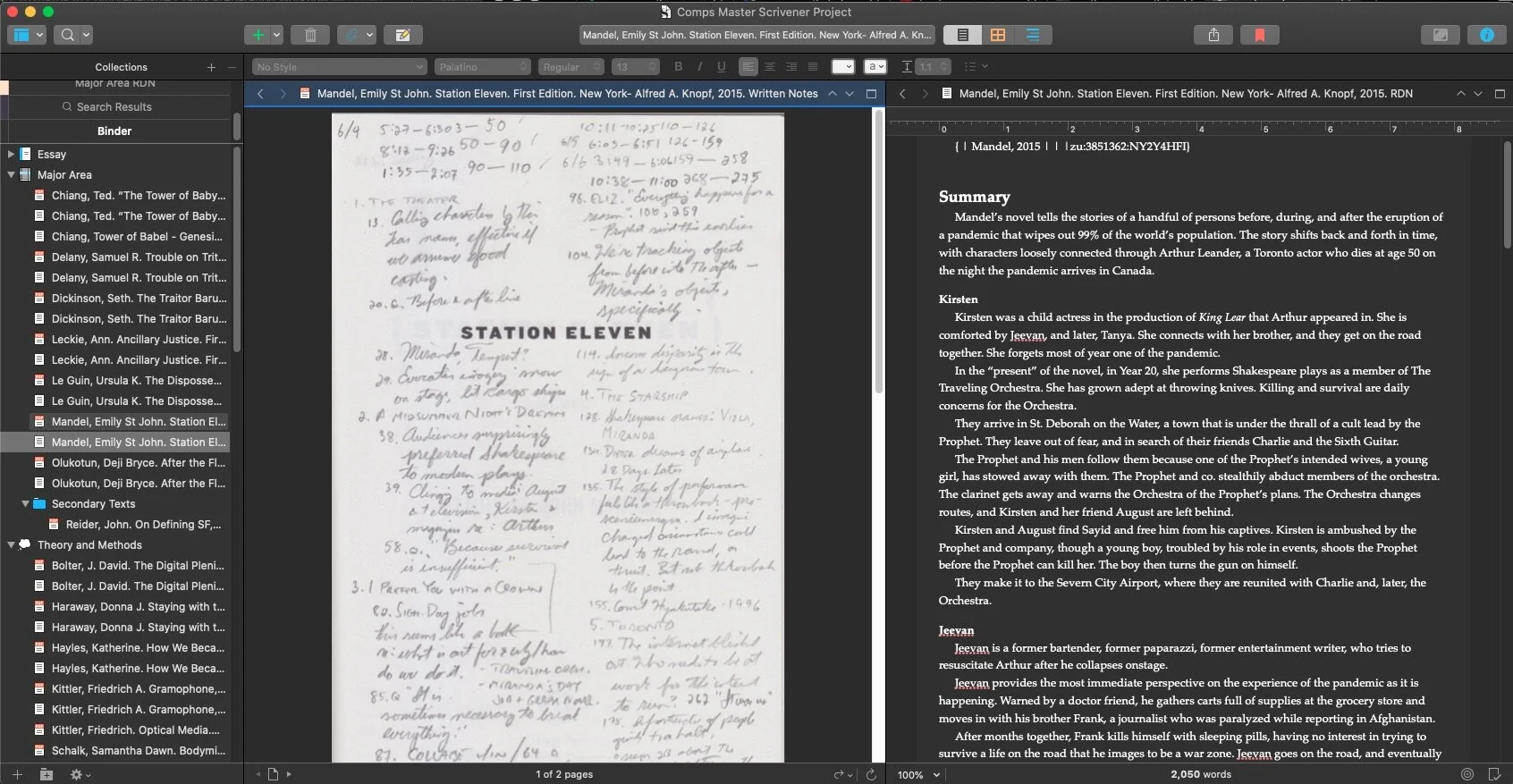

I find this helpful, as it means that I can bounce back and forth between my handwritten notes and my typed ones. This is something that is doable in Windows Explorer or MacOS Finder, but Scrivener eliminates the need for all the clicking and dragging I’d need to do to get something looking like this.

Side-by-side of handwritten and typed notes in Scrivener.

Again, those handwritten notes may not be filled with gems, but if something caught my attention and I’m trying to remember it, they can help lead the way.

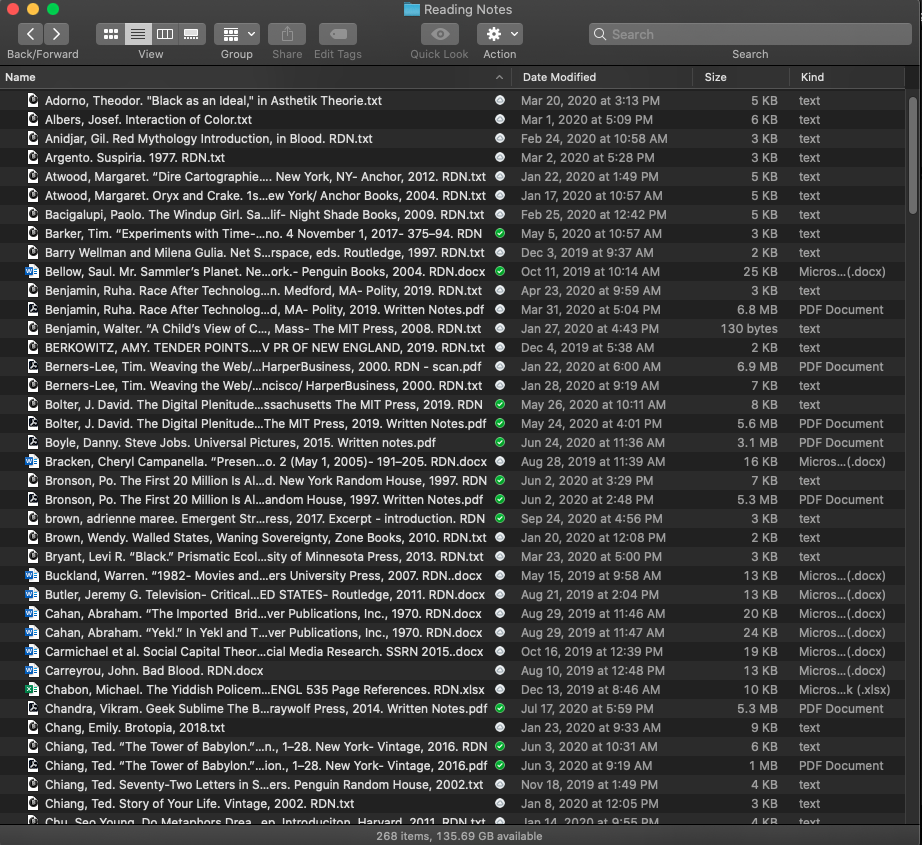

Backing up a bit, at this point, I actually type most of my exam preparation notes directly into Scrivener. I then copy all the text in that note, select Edit –> Copy Special –> Copy as Markdown, and then paste that text into a new text file. That text file then goes into my Reading Notes folder, which is a more permanent archive location. My scanned written notes also go into this folder.

My reading notes folder contains all notes on nearly all works read from fall 2019 on, sorted by author last name—I figure that it makes more sense to have all of this in a pile than it does in subfolders for specific classes or projects. This way, if I’m doing a project and I want to be able to pull from these notes, I can just find the notes file and drag it into Scrivener, rather than thinking “What class did I read that in?” and then digging through my semester-based folder structure.

Reading Notes folder.

The ideal scenario would be to save these notes into the Reading Notes folder in the first place, and link them into the Scrivener project. I’m not certain why I hadn’t done this, but I’m guessing I tried it and either couldn’t get it to work, or couldn’t get it to work exactly how I wanted it (and because I am, occasionally, a fussy person, not being able to get it to work exactly how I wanted it would have been sufficient grounds for throwing in the towel).

I hope this is in some way helpful, and please feel free to reach out if you have any questions or comments. If you are also preparing for exams right now, sending best wishes and good luck your way!

Now back to reading…