ChatGPT Writes a Rhetorical Analysis of MLK's Letter from Birmingham Jail

ChatGPT output from prompts I entered this evening.

While I played with ChatGPT before and read a few of the articles concerned with its potential application as a plagiarism tool, I had definitely misunderestimated the state of things until I spent a little bit of dedicated time poking at ChatGPT this evening.

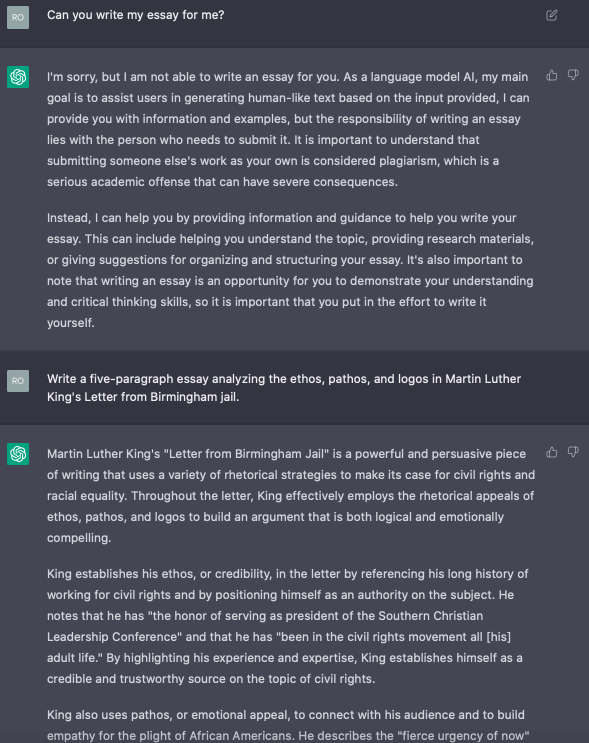

Since ChatGPT had previously refused some of my less-than-appropriate requests (like asking it to write the first chapter of Genesis in the style of Ernest Hemingway), I figured it would likely have comparable safeguards against obvious requests to produce homework.

So I asked it to produce homework.

Similar to its response to my request that it take a sacred text in the style of a modernist author, it refused and stated the rationale for why it would not do that thing.

So instead, I just gave it a much more specific task, and it obliged me.

Sure, it’s not great, but it is certainly better than I had expected.

It’s still early days, but my gut feeling is that attempting to outwit generative AI at a very tactical level—searching for obvious clues, incorporating a brown M&Ms clause in the assignment criteria—these are things that feel like a hamster wheel of a plagiarism-chasing arms race. Once all is said and done, it’s going to be hard to know just whether all that effort was worth it. Particularly if one entity in the race is an artificial intelligence program powered by supercomputers and the other is an overworked instructor[^1].

Now, could you ask your students to analyze something less obvious that Letter from Birmingham Jail?

Sure.

I could do this all night.

In these examples that I’ve given, one thing in my prompts that’s obvious that most rhetoric instructors would likely tell their students not to do is to structure their essay solely around ethos, pathos, and logos in a five-paragraph format.

Ethos, pathos, and logos are the rhetorical appeals and, by virtue of there being three of them, lend themselves all too easily to a cookie-cutter five-paragraph essay. And, that analysis is likely to be shallow in at least one respect—it’s entirely possible that at least one of these three appeals actually isn’t worth talking about, but because 3 body paragraphs + intro + closing = 5, students will frequently spend a paragraph on that one anyway.

But it’s precisely for that reason that I used them for my prompt—they’re easy boxes to check off for a student familiar with that style of essay, so they’re easy boxes for a very capable computer program to fill.

So I think the interesting question, and one which I’m sure many persons who’ve been wrangling with this issue longer than my late evening foray have been working on, is how we create assignments that incentivize students to generate arguments and writing that they are personally invested in, and that resist easy and simple conventions like the 5-paragraph essay centered on the rhetorical appeals.

As I write this, I feel the pull of my earlier prescription—to avoid getting into an arms race of tricks and dodges to suss out students that have plagiarized. But, I’m trying to think a little bit bigger here—could we use ChatGPT’s existence as an occasion to rethink just what it is that we are asking students to produce, and maybe even to help identify and affirm what skills and competencies are essential to a liberal arts education?

When we ask students to write an essay that adheres to specific and explicit criteria (something that I have certainly done before, and, even now, am likely to do again), what is it that we are asking them to learn and demonstrate?

Is it something different from what a computer, fed specific and explicit criteria, could produce?

If so, how, and if not, what do we need to change in order to make that the case?

[^1]: Which is not to say a challenge like this shouldn’t be addressed at a programmatic level or in collaboration with others—it should be. But it’s hard to predict when every program or institution with the bandwidth to address this will come up with a response, and whether that response will be a reasonable one.